Stand Off at Kakma: The Intricacies of Peacekeeping in Croatia, June 1994. Mike Vernon

WARNING: Due to the nature of the conflict and operations in the Balkans, some of these veterans' stories may contain graphic or disturbing content. Please use your discretion. If a story adversely affects your mental health, consider seeking help by consulting the agencies listed in the Resources section of this website.

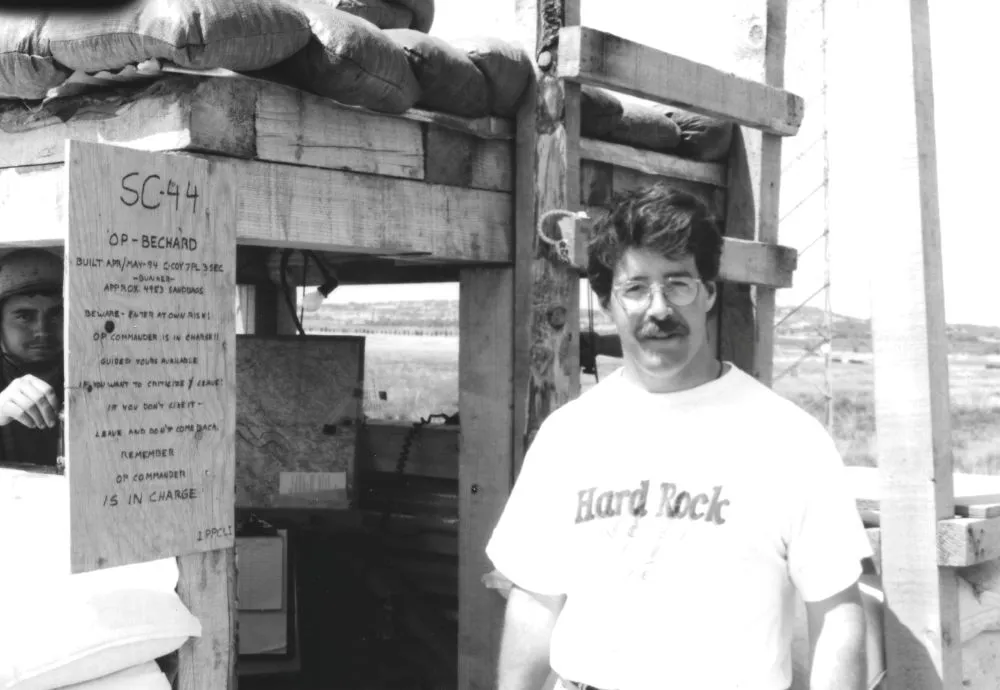

Mike Vernon at Observation Post (OP) SC44, Croatia, June 1994.

The author was embedded as a freelance journalist with First Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) in June 1994, shortly after he retired from the Canadian Forces as a captain in that regiment . This article was written in July 1994. An abridged version was published in the Toronto Star.

The citizens of Kakma are a community with little faith in the peace or the peacekeepers. The Canadian soldiers dedicated to defending them are professional but becoming increasingly frustrated by the petty realities of peacekeeping in southern Croatia. The events leading up to 22 June's [1994] stand off explain why.

Two soldiers man an observation post in Croatia, 1994.

Background

Kakma is a Serb village located within the zone of separation that divides Serbs and Croats in southern Croatia. This band of territory stretches along the internal borders of Croatia and the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina. United Nations soldiers, in this area Canadians, are responsible for keeping it demilitarized. At its narrowest, the zone of separation is two kilometres wide; in places it bulges out to five.

Kakma has been an ongoing concern for First Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (1 PPCLI), designated CANBAT 1 within the UN Protection Force (UNPROFOR), since it began enforcing the latest ceasefire 4 April.

The root of the problem is the Serbs' profound skepticism concerning the UN's ability to protect them when--it is not a question of "if" in their minds--the Croats attack again. The villagers are quick to recount how, during the Croat offensive (Operation MASLENICA) which began on 22 January 1993, French and Kenyan UN troops either withdrew or simply stood aside. As one Serb soldier said to me, "I can trust Canadian soldiers man to man, but I do not trust governments and the UN. Here I only trust my gun to protect me and my family."

Consequently, the villagers and the company of Serb soldiers resident among them--essentially a local protection force--want to have their village removed from UN protection and to see the zone itself extended two kilometres into what is now Croatian territory. This would permit Serb soldiers to wear uniforms and carry weapons openly in Kakma, behaviour that is contrary to the ceasefire agreement so long as the village is within the zone.

As a front line community, the citizens of Kakma are understandably preoccupied with their safety. They are not inclined to put their faith in the earnest Canadian soldiers who tell them "trust us, we're different." (Indeed, soldiers of 2 PPCLI fought back against Croat forces during the Medak Pocket operation in September 1993). The Serbs have already sworn they will turn their guns on their erstwhile defenders should they attempt to withdraw like their predecessors in the face of a Croat attack.

In addition to this threat, the people of Kakma have demonstrated their militancy in several other ways. The water pumping station adjacent to their village is of regional importance. Although it has the potential to pump water to the Croatian side, water has not flowed in that direction since the fighting began in 1991. In early June someone used explosives to destroy a section of the pipe leading to Croat-held Biograd.

Canadian soldiers construct prefab trailers, Croatia 1994.

The Serbs are adamant in their refusal to be "occupied" by UN soldiers, and this includes protesting the presence of Canadian patrols through Kakma. After the pipeline was damaged, the UN attempted to demonstrate its presence by erecting a prefabricated trailer in the middle of Kakma to serve as a sub-station for a UN civilian police (UNCIVPOL) detachment. This, it was felt, would not be as provocative as soldiers patrolling the streets. Left unattended its first night, the trailer was blown up, probably by an anti-tank mine.

The Plan

%20surrounded%20by%20Serb%20soldiers%2C%20Kakma%202.webp)

MGen Kotil (smiling in centre) surrounded by Serb soldiers, Kakma

Consequently on 18 June the UN commander of Sector South, Major General Rostilav Kotil, a Czech, arranged with the commander of the Serb North Dalmatian Corps for Canadian troops to restore the pre-ceasefire status quo in Kakma. The troops from CANBAT 1 would do this by constructing another UNCIVPOL trailer on the site where the first had been blown up, raising the UN flag over the water pumping station, establishing an observation post adjoining the pumping station's fence, and repairing the damaged water pipeline leading to the Croat side. There was no suggestion that the UN would then pump water to the Croats; just that the pipeline would be restored to its pre-ceasefire condition.

The operation was to commence at 8 a.m., 22 June, with Canadian combat engineers doing preparatory work the day before by clearing mines from a path adjacent to the pipeline and constructing the UNCIVPOL trailer. The operation was to be overt in every respect and Canadian officers expected the Serbian military chain of command to advise its company in Kakma of what was in the offing.

Prelude to the Operation

%20MGen%20Kotil%2C%20LCol%20Diakow%2C%20Capt%20McIntosh%20at%20Kakma%2C%2022%20June%201994.webp)

(L to R) MGen Kotil, LCol Diakow, Capt McIntosh at Kakma, 22 June 1994.

While CANBAT 1 geared up for the operation, Serb soldiers from Kakma patrolled within the zone of separation in violation of the ceasefire agreement. Soldiers from C Company (1 PPCLI) apprehended uniformed Serbs armed with assault rifles the evenings of 19 and 20 June. Their Kalashnikovs were confiscated and letters of protest sent to the local Serb commander by C Company's acting commander, Captain Keith McIntosh.

The morning of 21 June half a dozen Patricias worked to erect a three-sided blast wall for the UNCIVPOL trailer the engineers were constructing. The standard joke among them was that although the trailer would invariably be blown up, the blast wall would at least minimize damage to surrounding houses.

At the same time, engineers from First Combat Engineer Regiment in Chilliwack began clearing the patrol path adjacent to the pipeline. The grass in the area was a metre high, treacherous because of its potential to conceal trip wires and tilt rods that could detonate mines.

Three soldiers worked out front with a mine detector, prepared to use plastic explosives to blow in place any mines they found. An M113 armoured personnel carrier (APC) with a dozer blade followed to scrape and prove the route. The Canadians were unfamiliar with mine hazards in this area and were working without the assistance of Serb or Croat engineers, trusting to their equipment.

Shortly before noon, the APC detonated an anti-personnel mine wired to another which blasted a storm of fragments at the soldiers out front. A UN helicopter flying nearby in D Company's area was diverted for an aero-medevac.

When it landed, medics on the scene worked to reconfigure its interior to accept the two most serious casualties while infantrymen gave cardio-pulmonary resuscitation and artificial respiration to Corporal Mark Isfeld and monitored the others. Despite the speed of the evacuation, Corporal Isfeld died shortly after arriving at a Czech surgical unit in Knin.

%20MCpl%20Ken%20Taylor%20and%20Sgt%20Serge%20Cowen%2C%20Kakma.webp)

(L to R) MCpl Ken Taylor and Sgt Serge Cowen, Kakma.

Sergeant Serge Cowen and his section of five men, radio callsign 33A, were detailed to guard the UNCIVPOL trailer in Kakma that night and to conduct foot patrols through the town.

I accompanied the first patrol, with Sergeant Cowen and privates Robson and Wagman. We began while the locals held a large outdoor meeting on a soccer pitch 150 metres from the trailer. When it broke up, we were confronted by half a dozen young men, including the local company commander whom the Canadians have nicknamed "Lieutenant Jesus" for his shoulder length, blonde hair.

The first thing they wanted to know was the identity of the civilian with the patrol. "Croatian?"

Sgt Serge Cowen, Kakma, 22 June 1994.

"No, journalist," said Sergeant Cowen. I produced my press pass for scrutiny. The fact it had been issued in Zagreb was grounds for some excitement. I explained that UNPROFOR headquarters is in Zagreb.

Next they wanted to check the soldiers' weapons. Each man in turn cocked and canted his C7 to prove there was not a round in the chamber.

Then they asked that Robson, the radio man, carry his weapon slung over his shoulder instead of across his body, the normal position when patrolling. They thought it looked too aggressive.

As their last act they engaged Sergeant Cowen in a 15-minute "discussion" on the whole Serb-Croat conflict, the sort of lecture peacekeepers will hear many times during their tour. Finally we were allowed to carry on with our patrol.

Things were quiet that night, with only the occasional group of men in civilian dress walking the streets. Canadian Iltises drove the backroads around Kakma to confirm the Serbs were not continuing to do their own patrolling in the zone. They were assisted by soldiers at a nearby observation post, Sierra Charlie 44, using night vision equipment.

The Operation, 22 June 1994

Shortly after first light, Sergeant Cowen sent a situation report (sitrep) over the radio to C Company headquarters: "Three, this is three three alpha. Sitrep: I have ten armed and uniformed Serbs at a house 25 metres from my position." Those of us who had been in the process of waking up moved out from the shelter of the blast wall to see for ourselves. There were indeed ten Serb soldiers gathered across the road, armed with assault rifles, light machine guns, and rocket launchers.

Sergeant Cowen went across to speak with them and returned shortly. "They say that if we try to confiscate their weapons they have orders from higher to shoot to kill." Now we were fully awake.

For the next few minutes both sides observed each other. The Serbs varied in age, with the majority looking to be in their late-thirties/early-forties, with dark brown skin and wearing camouflage clothing. There was a younger clique that included the company commander, now wearing a flat-topped field cap, and an older man in a uniform that looked as though it had been issued during the Second World War.

While we watched, the radio inside the section's APC carried reports from other sub-units: armed Serb soldiers were appearing throughout C Company's area of responsibility--at the pumping station, in the bunkers outside it, 50 metres from observation post Sierra Charlie 45 on Mount Petrim, and at impromptu road blocks around Kakma.

Reinforcements continued to trickle in and within 15 minutes the Serb soldiers across the road outnumbered Sergeant Cowen's section by almost three to one.

Then something human happened to temporarily deflate the mounting tension. An English-speaking Serb with an unpronounceable name came across the street bearing a glass of rakije (plum brandy). "I don't usually drink before breakfast..." said one soldier as he acknowledged the hospitality by sipping the harsh liquid.

MCpl Ken Taylor with a Serb soldier, Kakma.

The Serb stayed to chat amicably about himself, his time as a paratrooper in Bosnia-Hercegovina, his parachute training, and the disco he planned to open in neighbouring Benkovac. Soon others drifted over to talk and compare weapons with Master Corporal Ken Taylor. They even swapped some of their stubby 5.56mm bullets for the Canadian equivalent.

Then they went one step further, asking for two litres of diesel - a very precious commodity in the Krajina these days--in order to send someone into Benkovac to buy some lamb for lunch. Sergeant Cowen authorized one of his soldiers to give it to them.

%20speaks%20with%20Capt%20McIntosh%20beside%20an%20Iltis%20at%20Kakma.webp)

LCol Diakow (left) speaks with Capt McIntosh beside an Iltis at Kakma.

Over the next hour, radio traffic increased. A UN helicopter began flying laps around the area. Captain McIntosh went to see the local Serb battalion commander to protest his soldiers' flagrant violation of the ceasefire. At this point, it was not known if the soldiers in and around Kakma were aware of the 18 June agreement and, further, whether they were acting on orders or against them.

An UNCIVPOL patrol in a white Jeep Cherokee stopped by to see their new home. Being unarmed, they prudently left once Sergeant Cowen had briefed them on the stand-off situation.

After seven o'clock, Sergeant Cowen lost patience with the social pleasantries and ordered his soldiers to refuse any further offers of rakije. (The Serbs had continued to drink from a gallon keg set on a wall across the road.) He pulled everyone inside the APC with their equipment. "If the operation goes in as planned," he told them, "we may have to get out of here in a hurry. They can have the trailer if they want it."

Pte Wes Friesen, M113 APC driver, Croatia 1994.

He addressed himself to Private Wes Friesen, the section's driver: "When I tell you to, drive straight ahead for the Croatian side hatches-down." Then he began giving orders to the others in the section, allocating targets for machine gun fire and grenades. The section members began to check and recheck their weapons and ammunition. [Someone offered me a grenade. I was tempted to accept it, given the situation, but since I had just retired from the Canadian Forces a month earlier I figured it wouldn't be appropriate for a civilian journalist to be armed. I declined.]

The 8:00 a.m. H-Hour was approaching fast and there were signs of confusion on the company radio net. Soldiers throughout the company knew how volatile the situation had become, but still no word had come down to postpone H-Hour or amend the plan. Captain McIntosh was still with the Serb battalion commander and unavailable on the radio.

Sgt Serge Cowen interviewed by TV crew, Kakma.

Sergeant Cowen radioed Sierra Charlie 44 for clarification: "I haven't heard a thing; is there a fucking plan or what?"

Across the street, most of the Serbs were lounging casually in the shade, but some were working the actions of their AKs and another was wiping down his bayonet. Their cook was gathering wood to feed the fire beneath a large kettle.

"Three three alpha, this is Sierra Charlie four four, assume the plan is to go as briefed last night--over."

"Three three alpha, roger--out."

There was not much for me to do but observe so I sat on the back deck of the APC with my legs dangling in the cargo hatch. Below me one of the soldiers had taken out a pocket notebook and was writing to his family: "Dear ______, I love you both very much..." I read over his shoulder. Someone else kidded Friesen, a Mennonite, he had about 15 minutes to do all the things he'd never done at Bible School.

And then, literally 30 seconds before H-Hour, Captain McIntosh came over the air and advised the company that their battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Mike Diakow, would be meeting with the Serb brigade commander to discuss the situation. The operation was off.

Within seconds, the tension everyone had been feeling was dissipated. "I told you," Private Monty Robson said with a smile. "Now they'll talk for the next four days and nothing will get done."

Friesen dropped the APC's ramp and the soldiers of 33A began digging in their German rations, looking for something familiar-looking enough to be edible. Crackers again.

The day became very warm. At ten o'clock the Serbs brought over two loaves of bread, two plates of boiled lamb, and a plastic bottle of coarse red wine. The lamb was greasy but delicious. It was still too early in the morning for red wine.

There seemed a strong possibility the whole operation would bog down in anti-climax when word came that the UN sector commander would meet in Kakma that afternoon with the commander of the North Dalmatian Corps.

%20LCol%20Diakow%2C%20Capt%20McIntosh%2C%20and%20MGen%20Kotil%20at%20Kakma.webp)

(L to R) LCol Diakow, Capt McIntosh, and MGen Kotil at Kakma.

Major-General Kotil arrived first and visited the pumping station with Lieutenant-Colonel Diakow. When the general's driver began videotaping soldiers at the gate to the pumping station an angry Serb harangued the general, demanding no taping, no photos. The Serbs are paranoid that unauthorized photos will be used for propaganda purposes against them. The video camera was dutifully stowed in the general's Cherokee.

Once the Serb officers arrived the official party departed for a private residence at 4:30 p.m. and didn't return until three hours later. By this time the tiny square near the trailer was full of expectant Serbs and UN soldiers, as well as European Community monitors in their all-white "Man from Glad" outfits, and UNCIVPOL officers.

Major-General Kotil, patrician yet friendly, ate a sandwich and took a few minutes to speak with the locals who surrounded him in a tight scrum before he headed off for more negotiations. A video crew from a Knin television station filmed with impunity.

In the end, nothing was agreed upon that night. The Serb soldier with the disco aspirations came back to say he had watched the Knin news report and that they thought the people in Kakma were in the right--no surprises there. The whole matter of moving the zone two kilometres into the Croatian area was tabled for discussion at the Central Joint Committee meeting between UN, Serb and Croat military commanders scheduled to commence the next day.

Sergeant Cowen's section was ordered to leave the trailer and move to Sierra Charlie 44 where all the Canadians in the area of Kakma were consolidating for the night. The Serbs patrolled Kakma itself, still armed. UNCIVPOL officers were reluctant to occupy the trailer until the situation improved.

A soldier uses a club to flatten sandbags as part of a blast wall at Kakma.

Aftermath

This sort of situation is increasingly frustrating to the soldiers of CANBAT 1. Invariably, their expectations and credibility are undermined when operations like this one are stillborn and degenerate into prolonged negotiations. There is an understandable reluctance on the UN's part to escalate too quickly or to use force when diplomacy seems the prudent course. Such caution, however, surely does little to convince the Serbs that the UN will demonstrate the resolve to stand in the way of a Croat offensive.

For their part, the Serbs play the UN well, with commanders making agreements and then conveniently stating they have no control over their subordinates' actions. They are also well aware that UN troops will turn about or stall in their tracks rather than run makeshift barricades or risk driving down roads the Serbs claim to have re-mined.

In all this the reaction of the Croats is the great unknown. Up until just recently when they began blocking the movement of UN supply convoys, they were quiet and seemingly patient. Certainly within CANBAT 1's area of responsibility they were adhering more closely to the ceasefire agreement than the Serbs. Pessimists among the Canadians believe they are waiting for the Serbs to do irreparable damage to the ceasefire with their petty violations, thus providing a pretext for a new offensive in the fall.

More than one month after the stand-off, nothing has been settled and Kakma is regarded as an ongoing ceasefire violation. Serb soldiers patrol in the town itself and the water pipeline has not been repaired.

Epilogue

In August 1995, the Croatian Army overran Serb Krajina during Operation STORM. According to news reports at the time, UN peacekeepers--Canadians included--stood aside as the Croat forces rolled through the zone of separation.

Have feedback or a story to share?